In 1728, there was only one act in town - and it was Handel.

If you wanted opera, it had to be Italian - gods and goddesses, nymphs and cherubs: it was all George Frederick Handel.

And then, along came a young man named John Gay with The Beggar's Opera - and nothing was ever the same again.

The Beggar's Opera was different - for a start it was in English; it didn't have any gods or goddesses, no shrieking sopranos - and there wasn't a shepherdess to be seen.

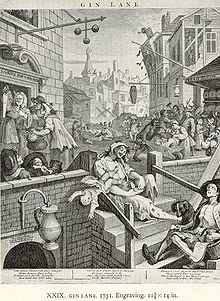

Instead, Gay had written about the low-life of London - thieves, vagabonds, pick-pockets, prostitutes, fences and corrupt jailers. It was the London he saw around him; it was the London that Hogarth painted - the London of The Rake's Progress, and Gin Lane.

No one had thought of doing that before. Gay's political satire was turned down by Colley Cibber at the Drury Lane Theatre (probably the biggest mistake in theatrical history), but courageously put on by impresario, John Rich, at Lincoln's-Inn-Fields. When the 'hero' of the piece was presented as a highwayman with pretensions of being a 'gentleman', everyone could see the political message Gay was sending about the then Prime Minister Robert Walpole. There was no mistaking Walpole in the character of the crooked, womanising Captain Macheath, and the public loved the play. In those days, there was no such thing as a long run - if a play lasted three days, then everyone was pleased - especially the author, who took the profits from every third performance as his fee.

But the Beggar's Opera ran for sixty-nine performances - an unheard of length of time - and so assured itself its place in history: it became the most popular theatrical piece in the eighteenth century.

The famous saying goes that The Beggar's Opera made 'Gay rich, and Rich gay.'

But it wasn't all plain sailing for the newly acclaimed playwright. Walpole got his revenge by banning Gay's sequel, 'Polly', and Gay died four years later. The epitaph on his tomb reads:

'Life's a jest, and all things show it. I thought so once, but now I know it.'